-

Biography

-

Milestones

-

Quotes

-

Photos

-

Learn More

Edna Irene Watson

August 2, 1895-March 1, 1976

One of Bermuda’s first two female MPs, social reformer, air crash heroine |

Photo: Bermuda Archives

|

World traveller, Cavalier crash heroine and war veteran Edna Watson had a distinguished record of service both in her native Canada and Bermuda. She and Hilda Aitken were the first two women elected to the House of Assembly in 1948.

A woman with vast stores of courage and a strong sense of adventure, she had two close brushes with death at sea, winning a bravery award for her role in the 1939 Cavalier plane crash, and a Royal Red Cross citation for her wartime service in Europe.

In Parliament, where she served from 1948 to 1953, she was the first woman to speak in the House and the first woman to chair a government board.

Six months after her election victory, she was appointed chairman of two Government boards, Transport Control and the newly created Board of Social Welfare, a hefty responsibility for a parliamentary neophyte.

While she won respect for her abilities, she became frustrated with Government’s reluctance to fund much-needed social programmes.

It resulted in her decision to found in 1951 the Committee of 25 for Handicapped Children, and in 1953, a hospital in Dockyard for children with disabilities.

Montreal

Watson was born on August 2, 1895 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, the eldest of three children of James and Eliza Webb. She studied physical education at McGill University in Montreal, graduating in 1917.

She joined the St. John Ambulance Corps in Toronto, where she got her start as a physiotherapist, treating soldiers wounded in battle in Europe during the First World War.

On November 30, 1921, she married fellow Montrealer, Air Force gunner Robert Beverley Watson. They visited Bermuda in 1924 and moved here permanently in 1927. In 1929, they built their home Scarrington on a four-acre property off Middle Road, Paget. The Watsons farmed the land and also raised poultry. In 1932, they added on four cottages to create Scarrington Guest House.

Crashed

Her life took a different direction following the death of her husband on April 21, 1938. Robert Watson, whose move to Bermuda was prompted by health reasons, was buried at St. Paul’s Church, in Paget. Later that year, she travelled to Montreal to spend Christmas with her family. The first leg of the return journey by way of New York went smoothly.

On January 21, 1939, she boarded Imperial Airways’ luxury flying boat Cavalier in Port Washington, New York for the five-hour trip to Bermuda. Two hours into the journey, they ran into trouble when the engine failed.

The plane, carrying eight passengers and five crew, lost altitude and crashed and sank within 15 minutes. Everyone on board managed to scramble out. There was no life raft, no flares and only six life belts.

The survivors formed themselves into a circle and clung on to the life belts, but within two hours, two passengers and crewman Robert Spence, slipped below the waters and drowned.

Rescue for the rest came just before midnight, nearly 11 hours later. The oil tanker Esso Baystown located the 10 survivors floating in the cold waters of the Atlantic. They were taken on board, and transported to the safety of dry land in New York and into the media spotlight.

Captain

Watson, aged 43 at the time, and one of three Bermuda passengers on the flight, was hailed as a hero for saving the life of the captain, Roland “Roly” Alderson. She helped keep him afloat after he lost consciousness, and buoyed the group’s flagging spirits during the long ordeal.

Grateful survivor Bermudian Nellie Smith—the other local was Catherine "Honey" Ingham—later told The Royal Gazette: “Mrs. Edna Watson was the life of the party. She absolutely kept us going, talking and joking.” The New York Times reported how Watson had swum among the group, “massaging muscles that had gone stiff with cold.”

Asked whether she was concerned about sharks, Watson told the New York Times: “No, nobody said anything about sharks. But all felt that with three dead, they might be attracted.”

Watson, along with Nellie Smith and the surviving crewmembers, sailed to Bermuda the following week aboard the luxury liner Monarch of Bermuda and to a hero’s welcome. She was escorted off the liner by the ship’s captain, Leslie Banyard.

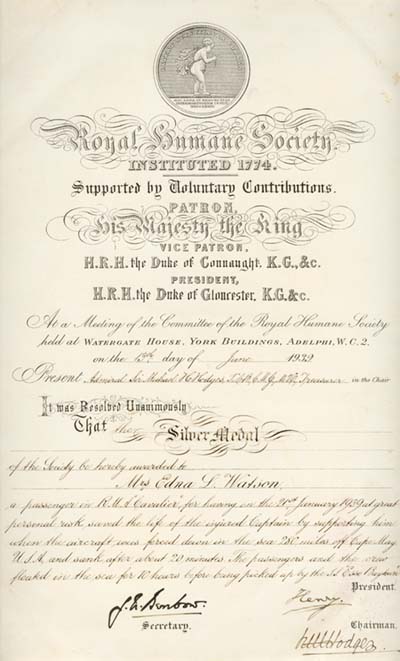

On August 4, 1939, in his last official act, Governor Sir Reginald Hildyard presented Watson with the Royal Humane Society’s Silver Medal, for saving Alderson’s life “at great personal risk” to herself, by supporting him after the plane went down.

(An inquiry later determined the crash was caused by ice on the carburetor and recommended the airline adopt new safety measures, including de-icing equipment.)

Captain Alderson never forgot Watson’s act of heroism. In February 1976, one month before her death, he visited her in Bermuda.

Ordeal

Unfazed by the Cavalier ordeal, Watson prepared to enlist in the Canadian Army following the outbreak of the Second World War. She returned to Canada in late 1939, took a refresher course in physiotherapy and signed up with the Army’s Medical Corps.

She was based in England for three years. In 1943, she was making her way to northern Italy, sailing in a convoy, when a German torpedo hit her ship and three others.

Her ship, which was transporting a large contingent of nurses and wounded soldiers, was badly damaged and eventually sank, but everyone on board was rescued. Watson continued on to her destination, where she helped care for casualties in makeshift hospitals which the Canadian army had set up throughout Italy.

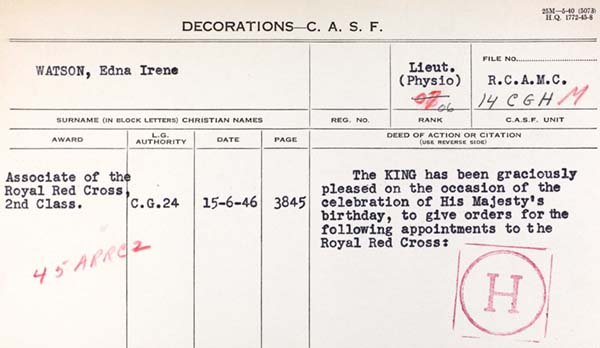

In 1945, Watson returned to Canada and set up the Department of Physical medicine at the Montreal Military Hospital (which became Queen Mary Veterans Hospital). In June 1946, she received a citation from the Royal Red Cross for her wartime service.

Suffragettes

That same year, Watson moved back to Bermuda and a new political landscape. Women property owners had won the right to vote in 1944, and voted for the first time in a 1946 by-election.

The 1948 general election saw four women vying for a seat in Parliament: Alice Scott, Frances Fox, Hilda Aitken and Watson. While Scott and Aitken had been actively involved in the 30-year campaign for voting rights for women, Watson had given little thought to politics up to that point.

Speaking to The Royal Gazette in July 1975, she said: “It was ten days before the election and some friends asked me to stand as a joke. I do remember that there was no Workmen’s Compensation at the time. I thought that was dreadful. On election day, I went to the polling booth and by the end of the afternoon, I was Member of Parliament for Paget. I had never even been to Parliament.”

When the ballots were counted in Smith’s on June 2, Aitken was successful. The Gazette headline the following day declared: “Mrs. R. Aitken Made First Woman Parliamentarian Here”. There was a second milestone on June 3 when Watson emerged a winner in the Paget poll.

Watson attributed her victory to her role in the Cavalier disaster. “People remembered the Cavalier and I had just returned from the Army,” she said. “That provided a bit of glamour.”

Appointments

Aitken and Watson were sworn in as Members of Colonial Parliament (MCPs are now called MPs) when Parliament reconvened on June 9. Businessman MA Gibbons was asked to stay on as chairman of the Transport Control Department even though he has lost his seat.

But when new board appointments were announced in January 1949, Watson was named chairman of TCD and a brand-new board, Social Welfare. (Board chairmen were the pre-1968 equivalent of Cabinet Ministers.)

TCD was challenging and contentious as cars remained a hot-button issue three years after the 1946 Motor Car Act allowed private cars on Bermuda roads for the first time.

Watson, who was chairman for five years, said she was given the job because no one else wanted it. Hers was a busy tenure. Licensing regulations for taxi drivers and car owners were drawn up under her watch, a new examination centre at North Street built and a safety campaign introduced. She also had to deal with matters that remain a concern today: more traffic accidents and noisy bikes.

Separate from TCD, she chaired a parliamentary committee that examined new uses for the railway right of way. The recommendations contained in her report, which was presented to Parliament in April 1950, laid the groundwork for the creation of the Railway Trail and the Trimingham Hill roundabout in Paget.

Improvements

Running the Social Welfare Board proved to be a source of frustration, she later said, because Government refused to fund social programmes.

One of its first projects was a fund-raising drive for renovations for Packwood Seniors Home in Sandys Parish. The project was a success, even though the work was not in its remit. More pressing needs such as a YMCA and other youth programmes and a home for children with mental and physical disabilities went unmet.

She stepped down after two years and Hilda Aitken replaced her as chairman in 1951.

Hospital

That same year she founded the Committee of 25 (‘for Handicapped Children’ was added to the name later). She invited 12 friends, who were asked to bring other 12 friends to the first meeting. Queenie Penboss, Doris Pedrolini, Yvonne Bowker, Rosemary Mitchell and Rea Wentworth are also identified as founders in the 1952 act that established the Committee.

In May 1953, the Committee opened the Children’s Convalescent Hospital in Dockyard to care for children with disabilities. It was an uphill battle. There was strong resistance to the hospital, even thought it was a godsend for working parents with limited resources and their disabled youngsters.

Initial fundraising efforts were successful. The old Royal Navy hospital, located at the water’s edge, was renovated. It was staffed by three RNs and eight student nurses, and cared for as many as 18 children at one time. Watson and her committee raised funds, and she also worked at the hospital one day a week.

Remarkably for the period, the hospital had an unequivocal no-discrimination policy for both patients and staff, a progressive and farsighted move in then segregated Bermuda.

Watson was described in a 1954 magazine article about the hospital as being “outspoken, fearless and resourceful.” It also said her “crusading drive” has stepped on “many a reactionary’s toes…”

Both Watson and Aitken ran again in the 1953 general election, but they were not reelected. Watson said she believed opposition to the hospital—which is now Lefroy Seniors Home—caused her defeat.

Paget voters may have also remembered her proposal at a parish meeting to purchase a tract of land on which to build 12 low-cost houses. The proposal was rejected outright.

Still, her defeat was considered a major loss to Parliament. No less than the archconservative House Speaker Sir John Cox said: “I consider the House of Assembly has suffered an immeasurable loss in her defeat. Her courage in tackling the boards on which she served has been quite remarkable and she was able to hold her own from the beginning with members far more experienced than she.”

Travel

After 1953, she devoted her energies to the Committee of 25, and also travelled widely, booking passage to far-flung destinations such as Egypt, Nepal, India, China, Japan and Bali on cargo ships. She frequently gave talks about her travels, wrote a book and even lined up an agent in hopes of getting it published.

In 1951, Watson sold Scarrington and moved to Harbour Lights on Harbour Road, Paget, after striking an ingenious deal with Bermudian landowner Sir Thomas Wadson that gave her life residency in the house she had built at her expense on his waterfront property.

Watson, who never remarried and had no children, relished her freedom. She told a reporter in 1961: “It’s wonderful being footloose and fancy free with no strings attached.”

Watson made a short-lived foray into the political arena in 1968 as a candidate for the Bermuda Democratic Party (BDP), which was formed by a group of disaffected Progressive Labour Party members.

The BDP failed to win any seats at the 1968 general election, which brought the United Bermuda Party (UBP) to power, and disappeared off the political scene.

At the unveiling of the BDP platform prior to the election, Watson said the government had never been willing to spend money on social welfare and that Parliament should thank women who had carried the load up to that point.

Political

After stepping away from politics, Watson occasionally spoke out about women’s issues. In 1966, she expressed concern about women’s reluctance to serve on juries, saying the suffragettes would have been ashamed.

“But in this day and age most women should think for themselves,” she said.“ I suppose their lives are too easy. They do not worry about a problem if it does not affect them directly. They are narrow in their outlook, not much travelled and not interested in political commentary. They are only interested in their general social lives and families.”

In 1975, she was a member of a panel that discussed equal pay for women.

When Watson died at age 80 on March 1, 1976, MPs paid tribute to her in Parliament. Government MP Dr. William Masters said she was a woman of great personal courage while Opposition Leader Walter Robinson described her as a pioneer for women’s recognition.

She was buried at St. Paul’s Church, Paget, where her husband Robert and mother-in-law Wilhelmina were buried years earlier.

Rehabilitation

In the years after her death, Watson’s accomplishments as a trailblazing Member of Parliament were overshadowed by her work with the Committee of 25. It provided provided crucial support to children with disabilities during its heyday, paying for overseas surgery, rehabilitation equipment and a pool at St. Brendan’s Hospital, where a children’s wing once bore her name.

In Parliament, portraits of Hilda Aitken and Lois Browne-Evans, who became the first black female MP in 1963, were installed at the House of Assembly, but Watson’s achievement remained unrecognised as she had long been regarded as the Island’s second female MP.

In July 2013, this oversight was corrected when a portrait of Watson—painted by artist Diana Tetlow and commissioned by the Paget Parish Council—was hung at the House of Assembly, between portraits of Hilda Aitken and Lois Browne-Evans.

Among those attending the ceremony was Jane Jackson, granddaughter of Sir Thomas Wadson, who said that Watson had entertained "the Paget scene with cocktails and dinner parties".

Watson was a socially progressive woman whose actions demonstrated an acute awareness of Bermuda’s racial and social inequalities and a strong desire to lessen their harmful effects. Her decision to align herself with the Bermuda Democratic Party instead of the United Bermuda Party ahead of the 1968 pivotal election indicated a willingness to go against the status quo.

Watson has no relatives living in Bermuda, but her legacy is kept alive by nephew Michael Hayes of Montreal, niece Anne Hillis of Nova Scotia, great-nephews Jaime and Andrew Hayes, Michael, John and Craig Hillis, great-niece Samantha Hayes-Babczak.

In Bermuda, her portrait is a tangible reminder of her pioneering work as a MP and as a founder of the Committee of 25 for Handicapped Children, which continues to carry out her mission.

|

August 2, 1895—Watson is born in Montreal

1917—Graduates from Montreal’s McGill University and signs on after graduation with St. John Ambulance in Toronto

November 30, 1921—Marries Air Force Gunner Robert Beverley Watson

1927–Settles in Bermuda following a visit to the Island in 1924

April 21,1938—Robert Watson dies and is buried in Bermuda.

January 21,1939—The flying boat Cavalier crashes in the Atlantic; Watson and nine other survivors are rescued 11 hours later.

January 30, 1939—Watson, Cavalier crew and fellow Bermuda passengers sail home aboard the Monarch of Bermuda and to a hero’s welcome.

August 4, 1939—Governor Reginald Hildyard presents Watson with the Royal Humane Society’s Silver Medal for helping to save the life of Cavalier pilot Roly Alderson

Late 1939—Watson returns to Canada, and joins the Canadian Army’s Medical Corps

1940-1943—Serves with the Medical Corps in England

1943—Rescued after the ship on which she sails to Italy is hit by a torpedo; Is rescued, continues on to her destination and treats soldiers in makeshift hospitals until the end of the war.

1945—Returns to Canada, and sets up the department of physical medicine at a military hospital in Montreal

1946— Receives a Royal Red Cross citation; returns to Bermuda.

June 3, 1948—Is elected to Parliament, one day after Hilda Aitken is elected

June 18, 1948—Receives “a warm ovation” when she rises to speak in Parliament for the first time

January 1949—Is appointed chairman of the Transport Control Board and the newly formed Social Welfare Board

1951—Steps down as chairman of the Social Welfare Board and establishes the Committee of 25 for Handicapped Children

1953—Fails to win reelection; Opens the Children’s Convalescent Hospital in Dockyard in May

1957—Children’s Convalescent Hospital closes because of lack of finances

1950s and 60s—Devotes her energies to the Committee of 25 and also takes trips to exotic destinations on cargo ships

1968—Is a candidate for the Bermuda Democratic Party in the general election; both she and the BDP are unsuccessful.

February 1976—Cavalier captain Roly Alderson visits her in Bermuda.

March 1, 1976—Dies and is buried on May 3 at St. Paul’s Church, Paget

July 19, 2013—Her portrait, commissioned by the Paget Parish Council, is hung at the House of Assembly.

“We formed a sort of ring holding up the ones in between who seemed weaker. For about an hour and a half after the plane disappeared the ocean was not very rough. The waves were only little ones but every once in a while a bigger one came along and bounced us.

"No, nobody said anything about sharks. But we felt that, with three dead, they might be attracted. Mr. Richardson swam away from and around us for a long time, and I found out afterwards that he was hoping to scare away any shark or hostile fish that might have been attracted to the scene.

“After a while, as it got darker, the waves got higher, but by then we had lost track of hours.”—Watson, speaking to the media following the Cavalier rescue, New York Times, January 24, 1939.

“Many of my friends approached me to run, but at first I turned the idea down. Then later I decided to stand, since women had complained until they won the right to vote and now it seems part of their duty to do their part in parliament.

“I believe in free, compulsory education, and I feel strongly that possibly insufficient effort has been made to train our people both, white and coloured, for the main business of our islands, that is, the hotel business.

“We would be more prosperous if we did not need to employ so much outside help. I believe that if children were started early enough they could, with expert teaching, have their education channeled into the paths that would mean prosperity for them and the Islands as a whole.”—Watson, announcing her bid to run for Parliament, The Royal Gazette, May 28, 1948

“We none of us wish to see Bermuda a welfare state with our citizens cared for from the cradle to the grave. It stifles initiative apart from being very costly, but no society should consider itself enlightened which does not adequately care for its handicapped, its needy and its old.”—Watson, unveiling the Bermuda Democratic Party platform, The Royal Gazette, December 13, 1967

“Half were on your side and half were not. You soon got to know who your friends were and who your enemies were.”—Watson on the challenges of being TCD chairman, The Royal Gazette, July 29, 1975

Edna Watson (right) was the oldest of three children. She is pictured with her parents Eliza and James Webb, brother Harold and sister Muriel. |

Portrait of Edna Watson as a young woman |

Edna Watson on her wedding day. She and Robert Beverley Watson (left) were married on November 30, 1921, in Montreal.

|

Edna and Robert Watson moved to Bermuda in 1927

and lived at Scarrington (right) in Paget.

All photos above courtesy of Michael Hayes and Jaime Hayes |

|

Cavalier rescue heroine Edna Watson is escorted off the Monarch of Bermuda by Captain Leslie Banyard. Photo: The Bermudian |

Edna Watson in her Canadian Army Uniform. She served in England and Italy with the Army’s Medical Corps from 1939 to 1945. Photo courtesy of Michael Hayes and Jaime Hayes |

|

The Watson grave at St. Paul’s Church, Paget where she, her husband and mother-in-law Wilhemina are buried.

[Left] Watson received a bravery award in 1939 for her role in the Cavalier plane disaster and a Red Cross citation in 1946 for her service during the Second World War. |

At home at Harbour Lights, Paget, where she lived from the 1950s.

Photo courtesy of Michael Hayes and Jaime Hayes

|

This portrait of Edna Watson, painted by artist Diana Tetlow and commissioned by the Paget Parish Council, was hung at the House of Assembly on July 19, 2013.

Photo courtesy of Paget Parish Council |

Further reading

Reports of Cavalier rescue and aftermath, New York Times, January 22, 24 and 31, 1939, March 28 and August 4, 1939; The Royal Gazette, January 23 and 30,1939 and August 5, 1939

“Ladies in Assembly”, The Bermudian, August 1948

“Scarrington… Paget”, The Bermudian, July 1954

“All Mankind’s Concern”, The Bermudian, July 1954

“She’s Had Many, Many Varied Experiences!” The Royal Gazette, February 4, 1961

“Suffragettes ‘Would have been Ashamed’ of Jury Lethargy”, Mid-Ocean News, September 17, 1966

“Today’s Woman: Mrs. Edna Watson”, The Royal Gazette, July 29, 1975

Edna Watson obituary and tributes, The Royal Gazette, March 2 and 6, 1976

“Committee of 25 Look Back on the Year”, Bermuda Recorder, June 23, 1973

“A political pioneer gets her due,” The Royal Gazette, July 20, 2013

Additional Sources

Transport Control Department and Board of Social Welfare Annual Reports, 1949-1953

Conversation with Jane Jackson, September 2013, and email interviews with Michael Hayes, Edna Watson’s nephew, and Jamie Hayes, her great-nephew.

Editor's note:

In The Canadian Who's Who, Volume V 1949-1951 it is stated that Edna Watson attended McGill University and that she obtained a Physical Education Degree in 1917 and a Physiotherapy Degree in 1918. While McGill University Archives is unable to find any record of Edna Webb or Edna Watson in its files, it is highly likely that Watson studied under Enid Gordon Graham, a pioneering Canadian physiotherapist, who in 1917 introduced two new courses at McGill’s School of Education, Massage and Medical Gymnastics. https://parks.canada.ca/culture/designation/personnage-person/enid-gordon-graham.

|